[In a article for Whitewall Magazine, Meenakshi Thirukode reviews Construction of the Exotic, a recent photo series, by BhaktiCollective.com contributing writer Michael Bühler-Rose. Enjoy the article below. The entire series can be viewed at his website Michael Bühler-Rose. Kaustubha das]

Whitewall’s South Asian Art Expert, Meenakshi Thirukode, looks at Michael Buhler Rose’s recent photo series, “Constructing the Exotic.” Find out if his work is merely the continuation of the Orientalist fixation or the embracement of another culture?

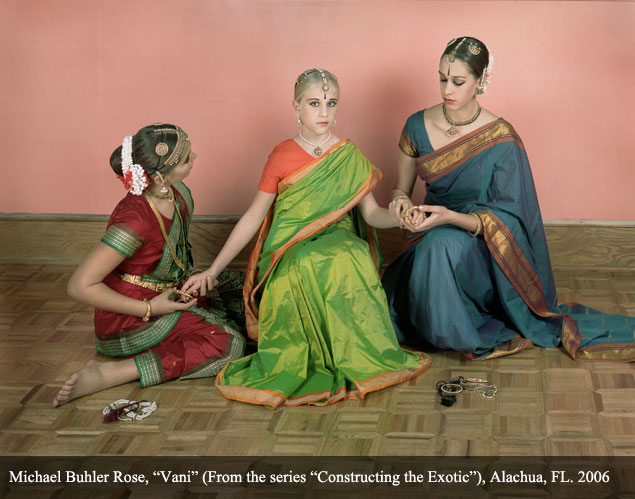

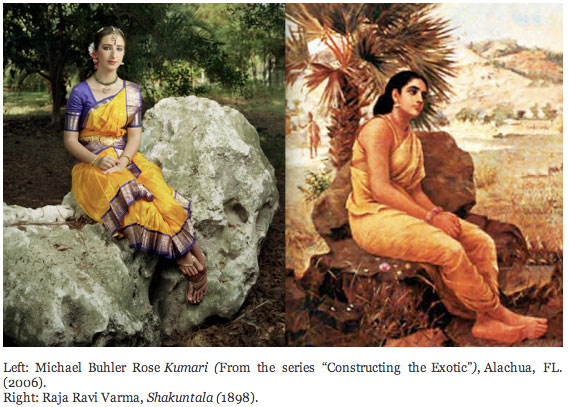

A strikingly beautiful young woman of European descent dressed in Bharatanatyam (a classical dance form that originated in Tamilnadu, in the south of India) costume sits poised on an ashen colored rock, the softness of her expression jarringly in contrast to the insentient stone. In another, two women attend to a young child. All three are dressed in traditional south Indian silk sarees, adorned with what are typical dancers jewelry – from the Nethi Chutti with its pendant like piece falling over the forehead to the Suryan (sun) and Chandran (moon), a pair of hair pins that sit on either side of the Neth Chutti. These are just two works from a series of photographs, titled “Construction of the Exotic,” by Michael Buhler Rose. One might think that from my point of view this could have come across as a white male artist continuing the Orientalist fixation of the “other.” It certainly crossed my mind, I wont argue against that. However, having grown up in Madras I, like most children, was initiated into the world of Bharatnatyam and Carnatic music classes by my parents, just as an American family might enroll their kids in ballet or piano lessons. There it wasn’t uncommon to see Westerners, coming from far away lands to learn and embrace our way of life. It is a community unto its own. So at the opposite end of my spectrum of interpretation, Rose’s women reminded me of just that.

When I met with the artist at his studio to discuss his work I came to realize that there was a key factor that had to be known to truly understand what his work entailed. Rose became a Gaudaya Vaishnava, popularly known as the Hare Krishna Movement in the West, when he was 14. The women in the series also belong to this community. He explains, “The women are second generation members of the Hare Krishna Community, some were born or raised in India, or somehow have inherited its cultural-religious heritage. They are for, the most part, of European descent and now live in a community in North Central Florida, just outside of Gainesville.” Representation and identity then become important in Rose’s work. The postures and compositions are carefully constructed and are reminiscent of the works of the 19th century artist Raja Ravi Varma, an artist that Rose is inspired by. In fact, the seated girl I first described was influenced by one of Ravi Varma’s paintings, Sakuntala (1898). This historical connection seems far more fascinating than a connection with Orientalism or exoticism within Western art history. What is interesting in this context is that in 1892 as the artist representing India at the International Exhibition in Chicago, Ravi Varma decided that it was his duty to show the Western world “the charm and sophistication of the Indian people whom ill-informed accounts had often made out as a primitive people and the white man’s burden,” (Venniyoor, E.M.J, Raja Ravi Varma, (Trivandrum: The Government of Kerala, 1981), Pg 30.).

The idea of identity has a long history within Indian art and is a large part of both Ravi Varma and Rose’s practice. In light of the societal metamorphosis that humanity has undergone, we live within a perspective that creates an efficacious tension within Rose’s work. In Ravi Varma’s time, the world was unabashedly clear in its biases and pre-conceived notions of different cultures. It certainly exists today but in an altogether different vein. Being far more of a heterogeneous realm today, we are constantly trying to be politically correct. What that creates is a sense of having a certain idea about people only to realize that your way off mark. That’s what Rose’s work does and it’s engaging. The artist belongs to a community and has embraced a certain culture and its ideology that is different from what he was born into.

The power of the image is important to Rose. He sees it within the religious and spiritual enquiries that exist as a precondition to his aesthetics in “how we read it, how it fits into history, and how we ritualize it.” For Rose, the religious is as important as his academic and artistic background. He makes regular visits to India, and has learned Sanskrit as well as philosophy, while focusing on particular ritualistic traditions, “For me and my particular faith, imagery plays a very important role, and because of that there is a lot of complex thought that surrounds the same questions I am asking in my artistic practice.”

In early works of still life’s he uses objects found in Indian stores that dot the geography of America – from DVD’s of old Bengali films to the mass produced pictures of the Hindu pantheon of gods and goddesses. The image of a deity, be it on a piece of paper or within the sanctum sanctorum of a temple, holds the same kind of power to the mass. The person who possesses this image finds that it reasserts whatever he might construct to be his faith. In much the same way Rose seems to play with that idea by taking an image and presenting it as art.

How these works are received has a lot to do with the context they are shown in. Of much more importance is what pre-conceived notions viewers will come with. With work such as this that has culturally specific influences there is the chance that many would make obvious assumptions. We have seen artists of Indian origin working as internationally recognized artists who feel completely uncomfortable being talked of from the perspective of their ethnic background or their denial to accept that their work has specific, non-Western influences. Rose has no such discomfort. However, the reasons for that are far more complicated. No matter what, if a South Asian artist was to be exploring this idea, it would most likely be called too “localized.” Rose doesn’t fit that description and in turn faces the possibility of criticism that’s easy and literal – occidental fascination of the other. That would mean the danger of walking away from it having gained nothing at all.

– Meenakshi Thirukode

Related Posts: Morning Rituals: Waking

Comments

2 responses to “Constructing the Exotic /A Review of the Art of Michael Bühler-Rose”

i am surprised that this is a work of eroticism in the 1st place. unless they mean the true realm of consentration and enlightenment. i am still so lost and trying to understand, but this art to me seems to imply complete enveploment in something beyond. i am a humble servant asking, please do not take this as arrogance.

Not erotic Crystal, exotic.